Visa: My First Mess

Like a lot of junior engineers, I started with the thing that gives you the biggest dopamine hit: frontends. Type a thing, save a thing, and there it is on your screen. Magic. I was hooked. At the time, AngularJS was still running half the internet, and people were okay with waiting five seconds for an app to load because TikTok didn’t exist yet and we still had attention spans.

At Visa, I got tossed into the glamorous job of rewriting a payment gateway UI. The stack was AngularJS + ASP.NET, which sounds like the setup to a bad joke, but in reality was just… slow. My task? Convert it to React. This was back when React meant class components, lifecycle methods, and “please don’t ask me about hooks because those don’t exist yet.” I proudly built features that I claimed worked (spoiler: they did not).

Eventually, CyberSource — another Visa subsidiary — wanted to do the same project. Months of my work were scrapped so I could join them. The upside: I finally had mentors. The downside: they wanted me to move to Austin. I turned it down, stayed put, and did what every stubborn junior engineer does when faced with a crossroads: I went down a rabbit hole of tutorials.

Next.js and the Cult of Buzzwords

At the time, Next.js was this shiny new framework. People said it was “the future of frontend.” In reality, it was just the pendulum of web dev coming full circle. Everyone who had sworn server-side rendering was terrible realized maybe it wasn’t so terrible after all — so they invented a fancy new word: isomorphic rendering. Voilà! Suddenly the thing we threw away was the thing we wanted back, except with more buzzwords.

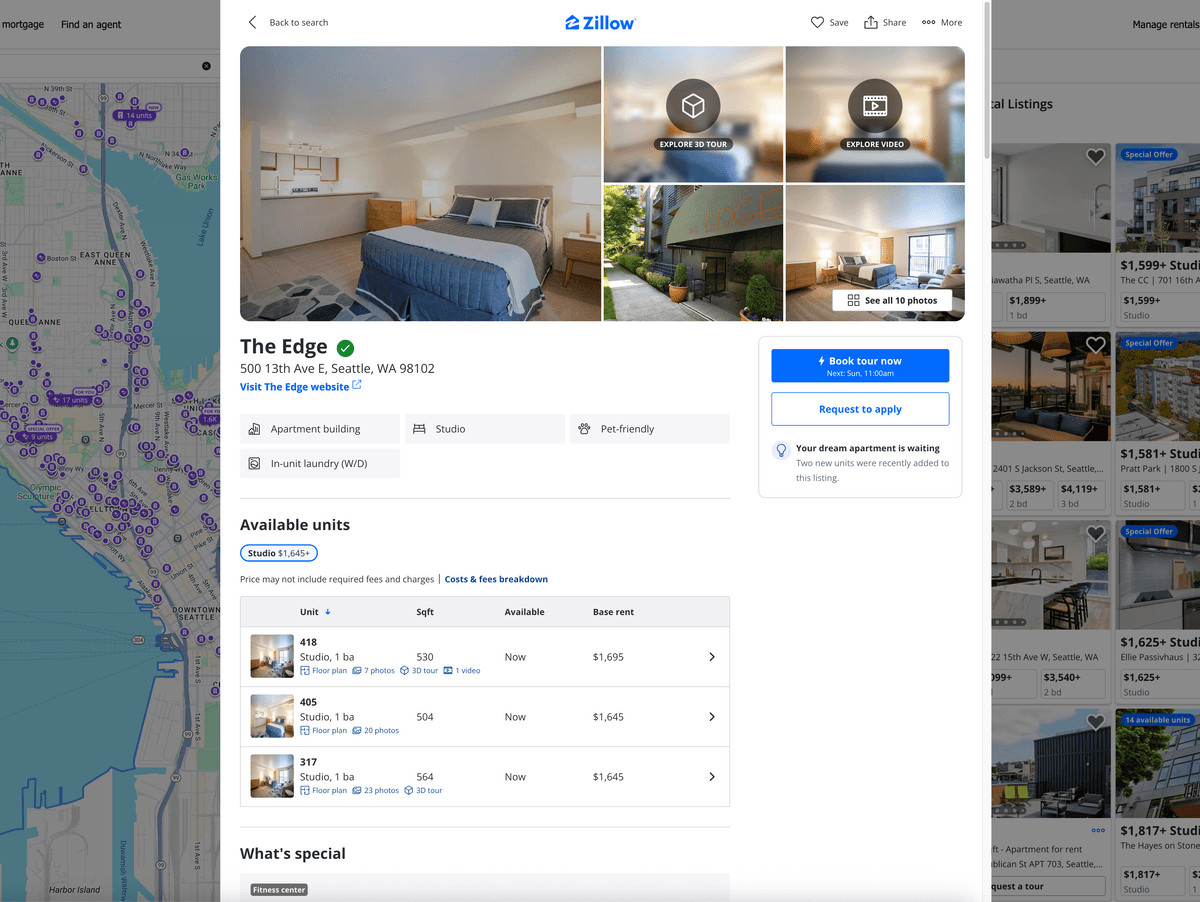

I taught myself just enough Next.js to be dangerous. By “taught myself,” I mean I occasionally opened the docs, half-watched a YouTube tutorial, and built a dummy app once a month before abandoning it. Somehow, this was enough to talk convincingly about React at interviews. And somehow, that was enough to land me an Associate Engineer role at Zillow. Apparently, the secret to breaking into tech is not mastery, but the ability to blabber with confidence.

Joining Zillow: Building for Millions

Zillow was the first time I worked on a product that millions of people actually used every day. I was a renter myself then, so working on the Rentals team meant I was basically building tools for… myself. For the first time, I felt like what I was doing mattered. More importantly, I had mentors who cared. If Visa was me fumbling around in the dark, Zillow was someone finally turning on the light switch.

I learned things that sound boring but are actually the difference between a good site and a great one: Search Engine Optimization, semantic HTML, accessibility. I discovered that using virtualization recklessly could hide content from search engines, which is a fun way to nuke your company’s Google ranking. I learned that milliseconds matter, that blurry tiny preview images exist for a reason, and that static precompiled pages beat the pants off pure client-side apps.

Sweating the Small Stuff (Because It Matters)

One of the more surprising lessons: sometimes your job is to work on the smallest, most microscopic sliver of a website. It can feel trivial, almost laughably so. But then you realize… those tiny details add up. A seemingly harmless experiment that causes just a -3% drop in traffic? That’s not “just.” At Zillow scale, that’s a lot of people suddenly not showing up.

So yeah, obsessing over milliseconds, alt tags, or the way an image blurs in before it loads might sound neurotic. But in reality, sweating the small stuff is how you keep users engaged, traffic healthy, and the business afloat.

Cutting-Edge and Over-Engineering

Then came the era of webpack 5 and micro-frontends. Our rentals page became a federated module, which felt cutting-edge at the time. (This was before Vite — before everything got “blazingly fast.”) Within a year, I was promoted and somehow became a “subject matter expert.” Which, if you’ve been following this story, is hilarious, because not long before, my “expertise” was pressing play on a Next.js tutorial video.

Looking back, what actually mattered wasn’t my ability to memorize frameworks. It was curiosity, humility, and mentors who let me screw up in public. My lead engineer would let me over-engineer solutions, watch me dig myself into a hole, and then gently help me climb back out. It was equal parts painful and invaluable.

The Moral of the Story

So yeah, that’s how I got hired at Zillow: a mix of half-baked side projects, overconfident blabbering, and the sheer luck of landing on a team full of people willing to teach me. The moral of the story? You don’t need to know everything. You just need to know enough to start — and the rest you’ll learn the hard way, one embarrassing commit at a time.